Common Traps to Avoid

Posted 1 April 2006

Errors in stainless steel fabrication can be expensive and difficult to resolve. So a 'Get it right the first time' approach to stainless fabrication is necessary to gain the best result. Check the ASSDA website regularly for a local Stainless Steel Specialist.

ASSDA Accredited Fabricators - Ensuring the Best Result

ASSDA Accredited Fabricators are companies and individuals that have a common understanding of successful technical practices for fabricating stainless steel.

To ensure the highest standard in quality, Accredited Fabricators belong to the ASSDA Accreditation Scheme, an ASSDA initiative that is intended to achieve self regulation of the industry, for the benefit of both industry members and end users.

The Accreditation Scheme criteria requires all fabricators to conform to stringent standards of competence, training and education, personal and professional conduct, adhering to a Code of Ethics and a Code of Practice, and committing themselves to continuing competency development.

The Scheme gives owners and specifiers of stainless steel greater certainty that fabrications using stainless steel will be performed by technically competent industry specialists.

COMMON TRAPS TO AVOID

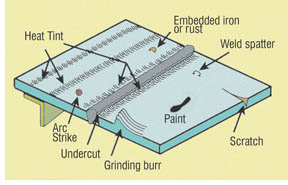

Surface damage, defects and contamination arising during fabrication are all potentially harmful to the oxide film that protects stainless steel in service. Once damaged, corrosion may initiate. Common causes of surface damage and defects during fabrication include:

Scratches and Mechanical Damage

Scratches and gouges form crevices on the steels surface, allowing entrapment of process reactants or contaminants, providing ideal locations for corrosion. Scratches may also contain carbon steel or other contaminants embedded by the object that caused the scratch.

Scratches will also raise customer concerns in situations where appearance is important. Mechanical cleaning is the most effective way to remove them. Prevention would be better.

SURFACE CONTAMINANTS

Common contaminants likely to attack stainless steel include carbon steel and common salt. Dust and grime arising during fabrication may contain these contaminants and should be prevented from settling on stainless steels.

Oil, grease, fingerprints, crayon, paint and chalk marks may also contain products that can provide crevices for localised corrosion and also act as shields to chemical and electrochemical cleaning. They should be removed.

Residual adhesives from tape and protective plastic sometimes remain on surfaces when they are stripped. Organic solvents should remove soft adhesive particles. If left to harden, adhesives form sites for crevice corrosion and are difficult to remove.

The most frequently encountered fabrication problem is embedded iron and loose iron particles, which rapidly rust and initiate corrosion. Other common sources of contamination are abrasives previously used on carbon steel, carbon steel wire brushes, grinding dust and weld spatter from carbon steel operations, introducing iron filings by walking on stainless steel and iron embedded or smeared on surfaces during layout and handling. All should be avoided.

WELDING

The high temperature characteristics of welding can introduce surface and other defects which must be addressed.

Undercut, spatter, slag and stray arc strikes must be minimised as they are potential sites of crevice corrosion. General cleanliness and removal of potential carbon contaminants such as crayon marks, oil or grease is important in obtaining good weld quality. It is also important to remove any zinc that might be present.

HEAT TINT AND SCALE

HEAT TINT AND SCALE

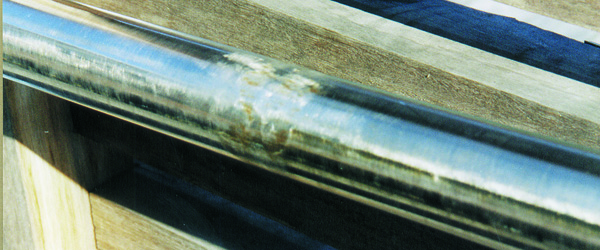

Heat tint and scale occur when stainless steel surfaces are heated to moderately high temperatures in air (3500C+) during welding.

Deleterious oxides of chromium may develop on each side and on the under surface of welds and ground areas. These oxides lower the corrosion resistance of the steel and during their formation the stainless steel is depleted of chromium. The oxidation and the portion of the underlying metal surface with reduced chromium should all be removed by mechanical, chemical or electrochemical means to achieve the best corrosion resistance.

DISTORTION

Stainless steel has a relatively high coefficient of thermal expansion coupled with low thermal conductivity, at least compared with carbon steel. So, stainless steel expands rapidly with the input of heat that occurs during welding and the heat remains close to the heating source. Distortion can result. Distortion can be minimised through using lowest amperage consistent with good weld quality, controlling interpass temperatures and using controlled tack welding, clamping jigs with copper or aluminium backing bars as heat sinks on the welds.1

REMOVAL OF SURFACE CONTAMINATION

REMOVAL OF SURFACE CONTAMINATION

There are three methods of repairing the surface of stainless steel.

MECHANICAL CLEANING

Wire brushing should only be done with stainless steel bristles that have not been used on any other surface but stainless steel. Clean abrasive disks and clean flapper wheels are commonly used to remove heat tint and other minor surface imperfections. Also effective is blasting with stainless steel shot, cut wire or new, iron-free sand (garnet is a common choice).

CHEMICAL AND ELECTROCHEMICAL CLEANING

CHEMICAL AND ELECTROCHEMICAL CLEANING

Embedded iron, heat tint and some other contaminants can be removed by acid pickling, usually with a nitric-hydrofluoric acid mixture or by electropolishing. These processes remove, in a controlled manner, from the affected areas, the dark oxide film and a thin layer of metal under it, leaving a clean, defect-free surface. The protective film reforms after exposure to air.

Passivation

Passivation involves treating stainless steel surfaces with, usually, dilute nitric acid solutions or pastes. This process removes contaminants and allows for a passive film to be formed on a fresh surface, following grinding, machining etc.

Care must be taken. Nitric acid treatments will remove free iron, but not iron oxide contaminants. Passivating, unlike pickling, will not cause a marked change in the appearance of the steel surface.

INSTALLATION

INSTALLATION

Stainless steel is best installed last to avoid damage during construction. Also, careful storage and handling including protective coating films are required prior to and during installation to minimise risk of damage to the stainless steel structure.

A primary goal of the stainless steel industry is to have finished products put into service in a 'passive' condition (free of corrosive reactions). Stainless steel is a robust and relatively forgiving material, but adherence to informed, good practice will ensure satisfaction for customers and suppliers alike.

Understanding stainless steel is important to its successful application. Ask your stainless steel representatives whether they have successfully completed ASSDA's Stainless Steel Specialist Course. Their commitment to product knowledge will be your key to success.

REFERENCES

1. NI & Euro Inox (1994) Design Manual for Structural Stainless Steel NiDI Ref. No. 11 013

RESOURCES

- AS 1554.6 'Welding Stainless Steel for Structural Purposes'

- Australian Stainless 2005 Reference Manual, ASSDA

- Stainless Fabrication Group, New Zealand, 'Code of Practice for the Fabrication of Stainless Steel Plant and Equipment'

- Nickel Institute (NI) 'Cleaning Stainless Steel Surfaces Prior to Sanitary Service'

- ASSDA - www.assda.asn.au

- BSSA - www.bssa.org.uk

- Nickel Institute - www.nickelinstitute.org

ASSDA acknowledges the assistance and contribution of Mr Peter Moore, Technical Services Manager of Atlas Specialty Metals in the production of this article. Photographs courtesy of Peritech and Outokumpu.

This technical article featured in Australian Stainless magazine - Issue 35, Autumn 2006.